Recently, I’ve read up on some of Anthropologist Dr. Fallou Ngom’s work, particularly his book, Muslims Beyond the Arab World: The Odyssey of Ajami and the Muridiyya. His book details the use of Ajami writing and documentation of various African communities alongside the rise of the Muridiyya Sufi order in Senegal.

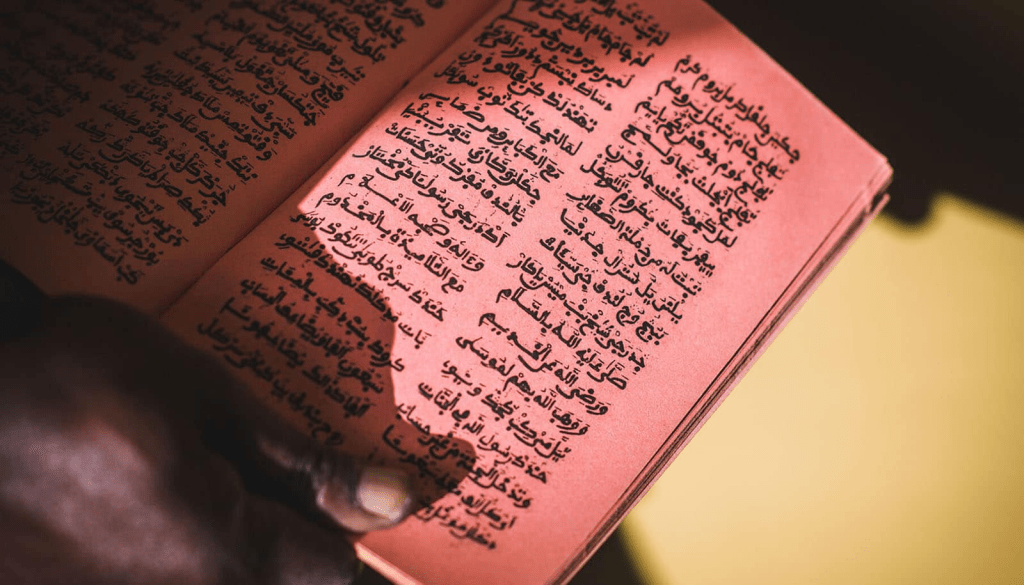

But what exactly are the Ajami Manuscripts and why do they matter? Well, these handwritten texts, often overlooked in mainstream accounts of African literacy, are a testament to how African societies adapted global influences—specifically Arabic script—to preserve their own languages, knowledge systems, and cultural practices.

Ajami (from the Arabic word ‘ajam, meaning “foreign” or “non-Arab”) refers to the use of the Arabic script to write African languages like Hausa, Wolof, Fulfulde, Mandinka, and others. This writing system dates back to at least the 11th century, emerging alongside the spread of Islam across the Sahel and West Africa. What fascinates me is how local scholars and scribes used Ajami not just to translate religious texts, but also to write poetry, record histories, draft legal documents, and share medical and astronomical knowledge.

In places like Kano (in northern Nigeria) and Timbuktu (in Mali), Ajami became a scholarly tool that blended Islamic teachings with indigenous knowledge. Hausa Ajami, for example, includes entire literary traditions—from epic poems praising local rulers to instructional texts on herbal medicine. This counters the myth that African societies lacked written records before colonialism. In truth, literacy in Ajami was widespread among Muslim communities well before the introduction of Western-style education.

What strikes me most is how Ajami manuscripts served as a cultural bridge. They preserved oral traditions in written form while embedding them within an Islamic literary framework. In my view, this challenges the colonial assumption that only Roman script counts as “real” literacy.

Today, scholars and archivists are racing to digitize and preserve these fragile documents. Projects like the Ajami Research Project at Boston University, headed by Dr. Ngom, are helping to catalog and translate these texts for future generations.

Perhaps what’s most important about these manuscripts is that they are more than relics; they’re living records of African agency, identity, and adaptation in the global Islamic world.

Leave a comment