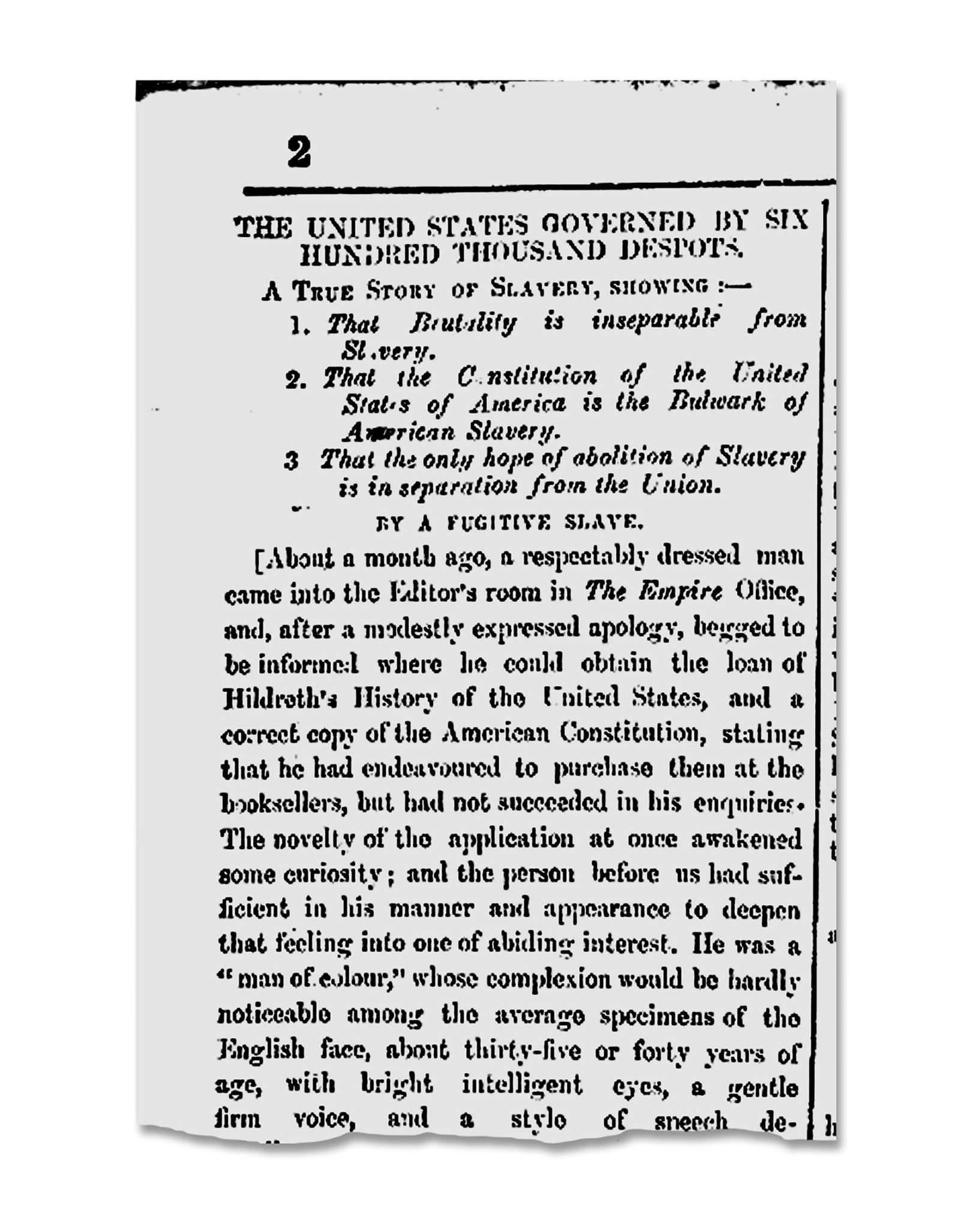

One of the most unsettling trends I’ve noticed in modern politics is the deliberate forgetting of history, a kind of national amnesia. Whether it’s erasing colonial atrocities, downplaying slavery, or recasting fascism in nostalgic terms, many societies are rewriting their pasts to serve present political needs.

Historian Tony Judt once said, “When the truth is replaced by silence, the silence is a lie.” That resonates with me deeply. In countries like the U.S., debates about history (Critical Race Theory, Confederate statues, textbook content) aren’t really about the past. They’re about who gets to define national identity.

Germany, for instance, took a very different route. After World War II, the country invested heavily in what it calls Vergangenheitsbewältigung -literally, “working through the past.” Holocaust education is mandatory; Nazi symbols are banned; memorials are prominent. While not perfect, this model reflects a willingness to confront and learn from historical evil.

Contrast that with Japan’s handling of its World War II legacy. There’s still political controversy over apologies to Korea and China, and many textbooks gloss over wartime atrocities like the Nanjing Massacre. The result? Lingering tensions and unresolved trauma.

Historical memory is not just academic, it’s moral infrastructure. When nations forget, they often repeat. When they remember selectively, they often marginalize.

The philosopher George Santayana’s famous line –Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”—rings true. But I’d argue there’s more: how we remember is just as important as whether we do. Selective memory breeds nationalism; honest memory builds humility.

I think confronting uncomfortable truths isn’t unpatriotic, it’s mature citizenship. And in our current moment of culture wars and revisionism, fighting for accurate historical memory may be one of the most vital tasks we face.